The elegance

(for Mr. Moore always looks a proper English gent)

acquires a touch of irony; it will do.

- Dilys Powell in the Sunday Times (July 1973)

Live and Let Die

Film: 1973 (#8)

Book: 1954 (#2)

Three British agents have died in a matter of hours, and Bond is sent to investigate. The trail either leads to the leader of the flyspeck nation of San Monique, one Kananga, or to the crime boss of Harlem (and apparently every predominantly black neighborhood in America), Mr. Big. Pick whichever you like, because they're actually the same guy. He's growing lots of poppies on San Monique and he's going to flood the American markets with heroin, gratis. The first taste is free, as they say. Several voodoo rituals and one long speedboat chase later, Mr. Big's schemes are proven to be somewhat inflated, and Bond gets ... Jane Seymour, which is not much of a reward.

Book vs. Film

First and foremost, Kananga is an invention of the film (see comments in Obscura). There is no San Monique. In the book, there is only Mr. Big, and while he basically owns Harlem, he has no interests outside of American gangsterhood, save a pirate treasure off Jamaica which British intelligence suspects him of smugging into the country and selling off to finance dubious activities. That's right, pirate treasure. The drug plot used in the film is a far more plausible one - in fact, Kananga's scheme to give away free dope is, as Bond says, fairly brilliant; the connection between an island prime minister and a Harlem gangster, however, defies belief.

It's also worth noting that this book is very early in the continuity, before Bond's second trip to the same Jamaican haunts in Dr No. Two characters Bond meets here, in the book, later get killed in the book of Dr. No; having killed them already in the film continuity, the film must invent new characters. Baines, who gets killed at the beginning of this film ("I rather liked Baines"), is actually supposed to be Strangways, the British station operative in Jamaica. "Quarrel Jr" is supposed to be Quarrel himself.

Felix Leiter loses at least one limb (the books are imprecise) after being dropped into a shark tank by Mr. Big's men; he goes through the rest of the books that way. In the films, the shark-tank sequence is transported intact (complete with the "he disagreed with something that ate him" joke) to License To Kill (and Leiter is never used after that in the films until the 2006 Casino Royale). The keelhauling sequence at the end of the book ended up being used, slightly modified, in the film For Your Eyes Only.

In general the book, despite the pirate angle, is better than the film, especially in the handling of Solitaire. She is, effectively, Mr. Big's captive. He believes she is a human lie detector, and too valuable to set free. She doesn't want to be in his custody, and the book makes this clear from the beginning; this makes her lack of agency, her defection to Bond, and her willingness to lie for him, all much more believable in the book.

Also, it's not clear whether she actually has any supernatural abilities, nor does anyone but Mr. Big really care. This whole business of keeping the power until she loses her virginity is an odious invention of the film, more so because it makes Bond really look like a right bastard, when in fact in the book his conduct toward her is consistently honorable.

The henchmen are better done in the film than the book, with the characters of Tee Hee and Whisper clearly defined (in the book they can hardly be said to be defined at all). Baron Samedi as a separate entity is an invention of the film; in the book, Mr. Big deliberately promotes the belief that he is Baron Samedi in order to coerce some of his followers.

Himself

I realize many people will consider this the beginning of a very long dry spell for Bond. Here's the thing about Roger Moore: It is very difficult to dislike him, and often as Bond that's exactly his problem.

One reason Moore worked so well as Simon Templar is that Templar is not, in bare print, a particularly likeable character (read some Charteris books if you don't believe me) - he's not always on the side of the law, even if he is always doing justice as he sees it, and some of his meddling and stirring-up-trouble tricks are outright mean. With Moore playing him, the character was always in our affections no matter what he got up to. But with Bond, that natural charisma sometimes softens the character too much. We must always hate and fear Bond a little; that touch of acid is important.

Moore almost never gets docked style points; he looks good in almost anything he wears, especially the stuff he designed himself. He seldom missteps as far as grace and charm are concerned. The problem is brutality. Eventually the writers would try to deliberately put him in situations where he had to be rough, to circumvent this; it didn't always succeed, and in this first Moore, they hadn't even learned the trick yet. Bond seldom even gets his hands dirty in this one, and the one time he does get rough it's with ... Rosie.

The Women

Bond's conduct toward the film's two key women is not great (as noted above, the stunt with the stacked deck is really a horrible thing to do - remember, by Solitaire's reckoning, he has just deceived her not only to sleep with her but to remove her powers and very likely endanger her life). On the other hand, the two women are written so badly that I can't get as worked up as I should. Rosie Carver is nothing but an annoyance from start to finish; her part mostly seems to consist of reactive screaming. She's an utter incompetence as both an agent and a double agent, and one might well be inclined to forgive Bond's condescension on the grounds of sheer impatience.

Solitaire isn't actively annoying; in fact, the problem with her is that she isn't actively anything. She contributes nothing to the plot whatsoever; even her fortune-telling is not, in the end, important, though much is made of it. She's there strictly for sex and rescue purposes, and it would take a better actress than Jane Seymour (which, admittedly, is a low bar) to redeem the character. As noted above, she's equally passive in the book, but the book does a much better job of explaining why.

For remarks on the race of these two characters, see below.

Backstory

EON began its search for a new Bond in earnest in 1972. Candidates reportedly given serious consideration included Jeremy Brett, perennial Julian Glover, and Michael Billington, not much known outside the UK, but a personal friend of Broccoli's. Billington would have been pretty good for the part - we shall see him in a different capacity later.

Moore, who had been ruled out for at least two previous films because of "The Saint," here almost got ruled out again because he was under contract for another season of "The Persuaders." However, the latter underperformed (especially on American TV, which apparently was where the major battlefield was - see also "The Avengers" and their ridiculous attempts to bend over backward to pander to an American audience), Moore was released from his Persuaders contract, and UA offered him a three-picture deal. He was 45; oldest Bond debut to date.

Broccoli was reportedly not entirely happy at Moore's casting; at least, not as happy as Saltzman was. This film was very much a "Saltzman film," with Broccoli barely present on set. (This will become more significant when we get to the next one.)

The rest of the production formula was altered very little from Diamonds Are Forever. Guy Hamilton returned to direct; Tom Mankiewicz did the script. Syd Cain did production design (but don't worry, we have not seen the last of Ken Adam). The only missing component from the usual suspects is John Barry; George Martin did the score. The loss is not felt; the score is very strong and ties in well with McCartney's theme song. One of my sources dislikes its long periods with no background music, but I find this improves the impact.

Catherine Deneuve was a strong early contender for Solitaire - once UA nixed EON's plan to cast a black actress in the role. (Mankiewicz reportedly wanted Diana Ross.) See comments below. This was essentially Seymour's film debut. Several sources claim Nikki van der Zyl dubbed some of her lines. Yaphet Kotto had already begun to make a name for himself by 1973; his most prominent film appearance before then had probably been in the original The Thomas Crown Affair in 1968.

David Hedison, an old friend of Moore, came in as a very good Felix Leiter; the friendship between the characters is genuine and works well, even if Leiter doesn't have a lot to do. Hedison's only other major film credit than his Bond appearances is as the hero (if that's the word) of the original The Fly.

"And how is Mrs. Bell?"

The Briefing

I am from Louisiana, and this may give me an unreasonable bias toward certain parts of this film. I like all the New Orleans scenes, I love the speedboat chase, and I admit a certain fondness for the cartoonish J.W. Pepper. (I dislike his being dragged into the next film, though.) None of this stops me from realizing that this film has not held up well. Some parts of it retain their impact - the pre-credits sequence of the three murders, especially in the way it leads into the title song, is still great - and others just sort of drag; some parts are actively embarrassing now.

This film was heavily influenced by the "blaxsploitation" trend, in full cry at the time, especially in the New York sequences. Certainly terms like "honky" and "pimpmobile" would never have emerged from Fleming's pen! It also shows a surprising amount of real-world relevance, with a drug plot (note that The French Connection had come out in 1971) and concern from the big players about the actions of tiny nations they suspected of being loose cannons and/or beds of insurgency.

Unfortunately, the film has a real problem with race, although not necessarily in the ways you might think.

I don't have a problem, for example, with the idea of a white hero and a black villain. This could have been misplayed and wasn't. Kananga is not villainous because he's black; he's villainous because he's a villain. Nor is he depicted with any of the more cliche characteristics - he's the best-spoken and possibly the most intelligent person in the film. (Incidentally, Yaphet Kotto claims that he was not permitted to do any press for this film because UA was leery of letting people know in advance that the film had a black villain.)

Strutter is a positive character; Rosie is a negative one but none of her negative aspects is tied to race; Quarrel is depicted well; et cetera. (Actually, the most condescending line in the film is Rosie speaking to Quarrel as if he's an idiot, an action from one non-white character to another.)

As for Bond, he successfully conveys throughout that he doesn't give a damn what color anybody is. His behavior in Harlem is clueless because he either doesn't realize his skin color will make a difference there, or is convinced it shouldn't. He has absolutely no issues working with Quarrel, Strutter, or Rosie. He certainly doesn't seem to be concerned about the color of whom he goes to bed with - which you may or may not consider a positive, depending on your feelings about promiscuity in general, but put it this way: Other people certainly did care. UA insisted Solitaire be played by a white actress because they feared the consequences of Bond having a black leading lady (we are still nearly thirty years from Jinx). Moore himself reported seeing the film in South Africa and finding that his love scenes with Gloria Hendry (Rosie) had been cut by the censors. Rosie, by the way, was originally intended to be white; Mankiewicz' script described her as a "beautiful, dazed white girl."

So where does the film go wrong? In the general attitude of white paranoia throughout. Every single black person but Strutter in Harlem is working for or cooperating with Mr. Big. Ditto apparently the entire population of San Monique (who are also often portrayed as superstitious and ignorant). The picture is filmed with what Public Enemy would later call "fear of a black planet," and it's this aspect that does the most toward making it difficult to watch in the present day. The worst racists in the film are the black characters who have "defected" to the white side - Rosie (well, while under cover) and Strutter - as if repudiating the "black planet" they have left. In addition to Rosie's treatment of Quarrel, Strutter's "spades" line is just hugely wince-worthy today, and I'd like to think it was in 1973 too.

The addition of the voodoo and supernatural themes muddies this water further. It's unclear whether Solitaire has any real powers, but she certainly thinks she does and so does Kananga; this belief is presented as a reason to ridicule both characters (Bond never at any point takes her fortune-telling seriously, and the audience is encouraged not to as well). Similarly, the voodoo rituals which are initially presented with sincerity are later revealed just to be a fake-out; a set of trap doors and a few tricks. Then, just as you believe you're clear on the film's stance (to wit, all the characters who genuinely believe in this claptrap are inferior, and most of those are black), one genuine piece of magic is left unexplained: Baron Samedi apparently really can't die. Depending on who you are, you either think this is an effectively spooky note to end on, or you think it's a disappointing let-down. (It may also depend on how you feel about the theatrics of Geoffrey Holder.)

Ah-ha-ha-ha!

Obscura

Ross Kananga is sometimes discussed in the context of this film as a "stuntman," but only in the sense that he did one stunt for the film. Kananga was an interesting fellow - an American Steve Irwin type who went to Jamaica to start a wildlife attraction - mostly crocodiles and alligators. He did his own gator-wrestling, and by all accounts was a little bit crazy. When the crew went on its scouting trip, they were intrigued by his place and its warning sign "Trespassers Will Be Eaten." The relevant sequence in the film was filmed on his property, and the running-across-the-gators stunt was performed by Kananga himself. It took him several tries and he nearly sustained serious injuries. As already noted, Mankiewicz honored this iconclast by naming his main villain after him. Kananga died in 1978, suffering a heart attack while spear-fishing in the Everglades (you'd expect nothing less). His original park lives on as the Jamaican Swamp Safari. There's a picture of Kananga in their pages.

This is one of the films which breaks the "always tell about the gadgets in advance" rule - the buzzsaw dial of Bond's watch is not revealed until he uses it. Demerit. The compressed-air-pellet gun isn't explained either, but don't blame Mankiewicz - his scene where Quarrel demonstrates its use was cut before filming.

Speaking of watches, it's difficult to imagine now how radical Bond's gigantic, press-to-activate digital watch was in 1973, but it was - it was obtained for the film by the ever-resourceful Charles Russhon. Russhon also obtained the clearances for the crew to get firearms from America into Jamaica, and arranged charter flights into Jamaica on 24 hours' notice. Such a useful person to have around!

Bond's espresso machine was also something of a novelty - certainly to American audiences - in 1973. I tend to agree with M's assessment of it.

It may surprise you to know that Moore was very insecure about this role, given his television successes. His film career, though, had not gone well to that point, and the cancellation of a second season of "The Persuaders" had badly shaken his confidence. "I realized three weeks before the opening: If this doesn't work, I'm finished," he later said.

Moore is actually driving the double-decker bus for a large portion of that chase sequence - he got some quick training before the film from a London city bus trainer, Maurice Patchett, who manned the bus for the actual impact with the bridge. Patchett said Moore took to the bus instruction quite readily.

Reportedly, it wasn't clear for a while that Bernard Lee was going to be available for the film; his wife had died tragically in a fire shortly before filming. This may partially explain why the M sequence, shot fairly late, is such an oddity among the Bond films. However, the producers also wanted to put some distance between Moore and Connery, which is probably why there is no Q scene.

Rumor has it that in the script, the speedboat chase is just written as "Scene 156: The most terrific boat chase you've ever seen." It pretty much is, in my book. The boat jump - 110 feet - stood as a distance record for some years. Some of Clifton James' reactions in the scene are genuine and ad-lib. The second boat was not supposed to collide with the police car, but it was deemed better than what they originally had planned, so they kept it.

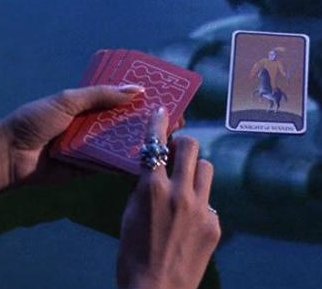

Have you noticed the 007 repeating design on the back of Solitaire's tarot cards?

"A man comes ..."

Doesn't it make you wonder where Bond got enough of them on short notice to stack the deck? Or am I thinking about this too hard?

« Heavy Bondage

« Opening Titles

All material on this site is under copyright by its author, except for quotations and images used for purposes of commentary (and which belong to their respective owners/authors). All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without express permission. Correspondence goes to projectionist at shrunkencinema dot com. No guarantees. Contents may settle during shipping; this product is sold by weight, not by volume.

These pages and their author have absolutely no affiliation whatsoever with Ian Fleming (Glidrose) Publications, EON Productions, Danjaq LLC, MGM/UA or any other creators of the James Bond novels or films.